My Cup Overflows

Fulness

Some of you will know (the others will be unsurprised) that I have strong opinions about certain words. For instance, I am adamant about jettisoning ‘busyness’ for ‘fulness’, and ‘productivity’ for ‘fruitfulness.’ Insisting on ‘fulness’ and ‘fruitfulness’ is one way of resisting the reduction of days to the harried futility of wind-chasing. The orientation of these words infuses apparent mundanities with awareness of the Giver: his gracious hand has filled my hands with precious gifts he would have me nurture and release again for the flourishing of life, as in so doing I return glory and gratitude to him.

With that in view, here are some of the beautiful things that have been filling my mind and hands of late: On the dissertation front, I am working towards the first-year review faced by every new Cambridge doctoral student, which will (successfully done) transfer me from being on PhD ‘probation’ to being a PhD ‘candidate.’ To this end, I am compiling an outline with projected timeline, bibliography, scope and methodology write-up, and 10,000-word writing sample to submit in May. Meanwhile I am progressing towards my personal aim of memorising the book of Job in Hebrew: with about 28 chapters down so far, I have 14 more to go!

Also Job-related, I had the opportunity to give a 45-minute presentation and Q&A at Tyndale House on 22 February. These weekly ‘Tyndale Talks’ are an opportunity for current readers (i.e., those with desks in the library) to share some aspect of their research and receive feedback. Entitled ‘Dizzying Doom and Gloom: Why Not to Skip Job 3–37,’ my presentation was not actually about my dissertation research. Instead, I decided to explore perhaps the chief obstacle that readers of the book of Job encounter: namely, that most of the book (at first) seems unnecessarily verbose, bewilderingly repetitive, and fairly dismal—frankly hard to get through. This talk, however, was my attempt to articulate something of how the structure and rhetorical strategies of the book of Job truly befit and enhance the book’s theology. In the interest of treading humbly (and as a marvellous heuristic), I think it best to assume that if we do not understand what a given biblical text is doing and why, that probably says more about our own ignorance than the text’s deficiency—and thereby ought to beckon us to be more thoughtful, patient students.

Other bits-and-bobs (one of my favourite British-isms): Ancillary academic endeavours have included writing some book and article reviews and submitting abstracts to present at upcoming conferences. Happily I was accepted to present a paper at the European Association of Biblical Studies conference in July… in Syracuse, Sicily (rough life, I know). Another Genesis Podcast episode in which I participated—an interview with OT scholar Jack Collins—can be heard here. After much prayer and conversation, I decided to switch local churches and have now launched myself into Holy Trinity, another vibrant Anglican church in Cambridge city centre; I have just joined the pastoral team of the undergraduate student ministry there. Term time (the present trimester being ‘Lent Term’) at Cambridge also brings fortnightly OT seminars in the Faculty of Divinity, German class, and occasional fancy dinners and transcendent live music.

As my hands cradle this fulness, my heart bursts in thanks to the Giver, and I pray that I might be faithful in stewarding all I am and have for the blessing of those he loves and has given me to love.

A foray to the Continent

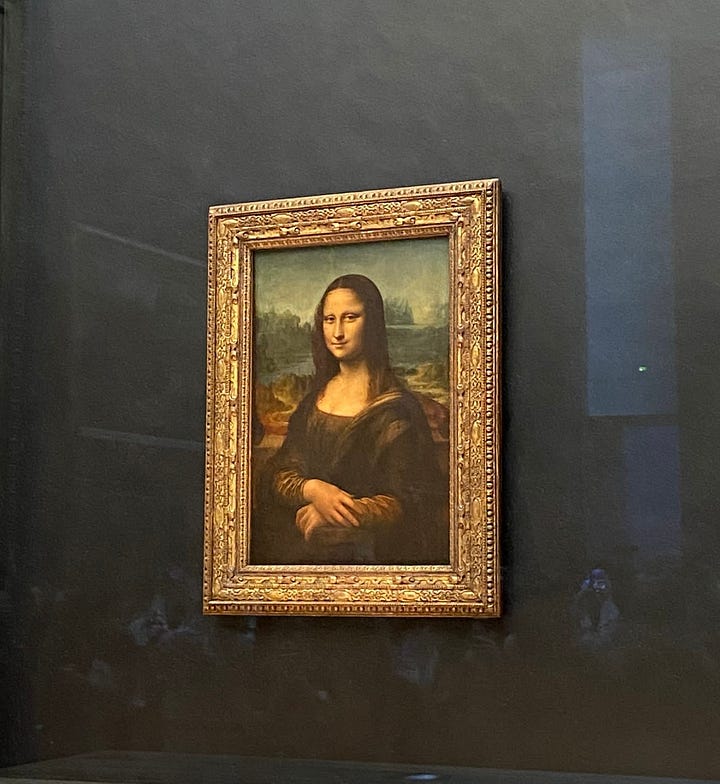

Upon crossing the Atlantic, it feels as though basically the whole world is on my doorstep. When I learned that my beloved uncle and cousin would be visiting France for a week from Australia, I simply had to pop across the Channel via train to join them for a long weekend in February. We blitzed around by foot and Metro to various iconic sites, relishing conversation and laughter all the while. As charming as it was, the setting paled in comparison to the rich vibrancy of the people with whom I enjoyed it.

More mulling

One evening as I ate dinner in my College canteen (Americans: ‘cafeteria’) with a non-Christian friend, this fellow first-year PhD student shared about her recent challenges with time commitments. I asked: ‘How do you decide the relative importance of things?’ Her instinctive response: what makes her feel good… and seems good for other people. Then came my genuinely curious next question: ‘And how did you decide that those two criteria were reliable and worthwhile ways of making decisions about how to invest yourself?’ Visibly surprised at herself for how previously unscrutinised this question has been for her, she responded that she has no idea how or why.

I heartily commend this dear friend’s candour. Much of the Western world is awash in cultural currents which insist that personal autonomy to self-actualise is primary, yet this posture is often imbibed rather than examined. According to this worldview, to submit would inherently impinge on ‘the good life,’ because then the self would not be sovereign. But then I must wonder if my own ostensible sovereignty is already fundamentally undermined: How can I be sure that I reliably intuit what is good and worthwhile (for myself, let alone for others)? What if my and my neighbour’s good seem to be mutually exclusive sometimes? Can anything even be said to be truly good in a life so fragile and fleeting, continually threatened by the spectre of death?

Those questions may seem shattering, but only to constructive end. In recent years, I have found bracing joy in rigorously (albeit imperfectly) training my delight on Who is worthy of it—not wishing to let it linger on the disparate ‘whats’ of fleeting fancy. It sounds nonsensical within our cultural milieu to be uncompromising in disciplining one’s desires; what a travesty to interrogate, even alter, how I feel! But herein lies one of many glorious paradoxes inherent to Christian discipleship. The Bible’s incisive perspective on the human condition is that we were made by and for a King who has himself stooped to servanthood to win back our allegiance. As I bow my knee in surrender, he tenderly lifts my face and crowns my head. In becoming willingly acquiescent servants of a loving Master, we together inherit an unshakable kingdom as his children. So submission is bound up with real freedom, and ‘the good life’ can only lie on the other side of a death. Knowing this King is life itself.

I realise that may have sounded hopelessly abstract. Though certainly I have yet to internalise these truths fully—oh, that I might!—I contend, my friends, that a well-aligned heart is eminently practical. It releases us to be neither over-awed by nor apathetic about our present predicaments. It calibrates us with compassion to the questions our image-bearing neighbours may not know they are asking, longings stirring within. It furnishes wisdom as we discern what is worth doing in our ‘one wild and precious life’ (per Mary Oliver). It tunes us for the song of the kingdom, such that our pining hearts may tenaciously hum it now and surge forth in a torrent of praise when at last the King returns.

And with that, I welcome you go for a walk—or hop on a swing—and ponder your overflowing cup.